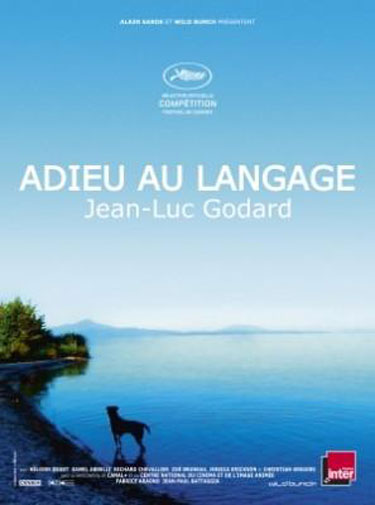

Festivals CANNES

Adieu au langage

Goodbye to Language

Length: 70 minutes

Director: Jean-Luc Godard

Actor(s): Christian Gregori, Héloise Godet, Jessica Erickson, Kamel Abdeli, Richard Chevallier, Zoé Bruneau

Writer(s): Jean-Luc Godard

Producer(s): Alain Sarde, Brahim Chioua, Vincent Maraval

| When the prizes were announced at this year's Cannes film festival, many were surprised that the Jury prize should be awarded ex aequo to "the oldest and the youngest film author" - Adieu au langage and Dolan's Mommy. What went unnoticed, however, amidst this frenzy of young/old polarity, is that 83-year old Jean-Luc Godard, with his Adieu au langage's innovative film language, original techniques, and radical departure from 3D as we (don't) know it, turns out to be the youngest of all film authors – "youngest" in the sense of his pioneering spirit, originality of his authorial creativity and artistic vitality, as if inaugurating yet another new wave, with "fresh blood" in film art. It was the film that could by no means be missed in Cannes.

And there is much blood in Adieu au langage. Blood that pervades the 3D "flatness" more than Pierrot le Fou, La Chinoise or Weekend. Blood that does not call for a revolution, but reminds of violence and death of all things. The end. We are reminded of perpetually repeated historical disasters ("Hitler didn't invent anything; numbers, decimals... had a long tradition before him or Machiavelli, Bismarck..."), of our permanent fear and persistent search for happiness ("Vous me dégouttez avec Votre Bonheur"), when everything falls apart. The status quo is there, yet the centre can't hold anymore. "Left and right have been turned around, but not the high and the low" ("le gauche et le droit etaient renversés mais pas le haut et le bas"). There is also a couple, love nudity, art and Mary Shelley writing by the lake in Godard's Switzerland. The couple is divided in separate shots and can't communicate anymore. "Only free beings can be strangers with each other, it's their freedom separating them." But the protagonist is a dog, who watches with us, who watches us and who IS with us, but we have yet to see this. The animals and nature "bleed" and the baby cries. It is the end of the human, maybe even of animals, of the dog the protagonist, a loyal and tortured companion to humans. The only hope of life in a posthuman world seems to be nature. "Forest means 'world' in Indian language". I do not intend to offer explanations or interpretations of the film to those who didn't understand it or who loathed it. To 'explain' it would only sacrilege this philosophical essay or visual poem, whichever way it's perceived. Those who didn't understand it should see it again and again until they understand it. I saw it only once, but would love to watch it again and again. Godard does it again, too: "I know what others think but not what I think". Those who have seen his short 3D film masterpiece Trois désastres, screened in Cannes last year, will be less shocked by Adieu au langage, which might look as the former's sequel, the only logical but uneasy sequel (then again, Godard is never easy, especially for non-French speakers, as most of his word plays are untranslatable). What may be more shocking is his choice of 3D technology, as he declared a war "on 3D dictatorship" in his previous film, in which he parodied, fragmented, decomposed and demolished the 3D image reality. Yet, in Adieu au langage, he returns to 3D, not only to decompose and destroy it, but also to explore it and deconstruct it in hitherto-unseen ways, only to finally denounce it as "bizarre", superfluous and unnecessary. In that sense, Trois désastres is better described as a prologue to Adieu to langage, Godard's final statement on 3D, to which he'll never return, I hope. As in Trois désastres, he doesn't only play his technical and narrative games in his typically ironic, elliptical manner with images, sounds, shapes, colours, lines and perspectives, he plays with words and almost untranslatable multilingual puns (e.g. usin-age), as usual. But instead of asking his questions on cinema, arts, civilization, history, human memory, communication, love and politics, he now ruthlessly asserts. Instead of suggesting as in Eloge de l'amour, Film socialisme & Histoire(s) du cinéma, he now states explicitly and directly, he 'explains' everything. It is the end of everything, but not of Godard, as some might like it. "Philosopher is the one who perceives the revolutionary force of signs we don't see" ("le philosophe s'appercoit de la force révolutionnaire des signes qu'on ne voit pas"). Death of metaphor and thought Whereas "words are here to express something that doesn't exist in the reality", words are not necessary anymore, as the reality is also gone in the age of limited space and characters set to express our thoughts, that don't exist anymore. He announces not only the death of semantics, morphology, syntax, phonology, but of film language, of image, reality, photography, communication, codes, signs and thought. |

"Images are becoming the murder of the present"

Painting was joussiance It is also a game of the visible and not visible, which may make the film hard to follow, but not incoherent. Everything is coherent in his clearest and most direct film so far if enough attention is paid. And that's precisely what Godard does: he asks for your attention – complete and devoted, which is hard in the age of rapid, superficial, mass, non-metaphor communication – sms, twitter, facebook, chat.... If we paid attention, we would understand the superimposed multiplied images and word games. Godard cannot be clearer: "It is not about the absence of what we see, but of what we don't see " "Un fait ne traduit pas comme un fait, mais ce qu'on ne fait pas" (an attempt at translation: "a fact doesn't translate as a fact, but as what is not done/fait").

He reinstates his "disaster" ideas of our search for more image reality, ending up with more illusory space-time than ever, seated in a dark cinema space with 3D glasses to watch a single screen. Thinking we are closer to the real, multiple screen realities multiply our illusions. "First films used 1 (camera) eye to be watched with 2 eyes, and now we use 2 eyes to watch 3D". If this was not understood in his short film, Godard clarifies it in his second 3D film, by destroying the 'reality of the human eye' and multiplying illusions: one image becomes two, then multiplies into three new and different ones, as mise-en-abime, not only within one shot, but with several shots brought together into a completely new image. One eye sees one shot of the scene and the other sees a different shot of the same scene simultaneously (through a dual projection system), thus assaulting the human eyes by making it difficult to choose which part to watch. This torture by multiplied mirror-like beauty (especially accentuated in scenes with 'real' mirrors mirroring human nude bodies) renders our choice of vision impossible and stresses the illusion of image-space in an unprecedented way. He wants to blind us: 'it's not the animal who is blinded, but the man is blinded by his conscience, he doesn't see the world". Mirrors are everywhere, yet nobody dares to look. "Everyone is afraid". "I know what others think but not what I think" More original, radical and direct than he – or anyone else - has ever been before, Godard, who made Histoire(s) du cinéma, seems to have exceeded himself and now makes a new history of cinema, by subjugating us to completely new visual experiences. He slices, dices, cuts, fragments, skips, superimposes, chops, dismantles, separates the sameness and unites the extremes. He is not sadistic only with images: he also experiments with our ears, by abruptly silencing loud music and as abruptly and suddenly raising the sound to new heights, but disconnecting the image from the sound, thus making a new assault on all our senses. As Jean-Michel Frodon says: "if there is a Nobel prize for film, Godard should win it, but there isn't". ("Pour ce seul plan, le chercheur Godard pourrait recevoir le Prix Nobel de cinéma –mais ça n'existe pas.") Maja Bogojević |