Retrospectives

THE YOUNG ONE: Buñuel’s Neglected Masterpiece

Let’s start with a dream scenario, a movie that might have been. What if Luis Buñuel made a picture with an American producer, American screenwriter, and American actors during the height of the civil rights movement and set it in the rural south? What if the main character were a jazz musician from the north fleeing from a southern lynching, falsely accused of raping a woman? And, to make a still headier brew, what if Buñuel decided to work in the theme of Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita, a recent best-seller — the deflowering of a young girl by a middle-aged man?

As a piece of exploitation, this hypothetical project fairly sizzles; yet in the hands of a poetic, corrosive, highly moral filmmaker like Buñuel, it might conceivably transcend this category. Allowing for the strangeness that naturally arise from a foreign director taking on such volatile American materials — indeed, a strangeness that might enhance the freshness of his treatment -—one could well anticipate the beauty and excitement such an encounter might produce.

The above scenario may sound far-fetched. But the fact is that what might have been actually exists, and has existed for the past half-century. Luis Buñuel did all the things I’ve mentioned in 1960, but hardly anyone noticed–and most of those who did were far from pleased. The New Yorker accorded Buñuel’s film a dismissive paragraph, the big Manhattan dailies were hostile, and, according to Buñuel, “A Harlem newspaper even wrote that I should be hung upside down from a lamppost on Fifth Avenue….I made this film with love, but it never had a chance. American morality couldn’t accept it. It hardly did any better in Europe and even today, it’s hardly ever shown.”

Symptomatically, the very first book to have been published about Buñuel in English, only three years after this film was made — Adrienne Foulke’s translation of Ado Kyrou’s study in French –doesn’t even pay the film the courtesy of mentioning its original English title, calling it exclusively (and inexplicably) La jeune fille. And coincidentally or nor, this parallels the denial in Franco Spain that Buñuel’s next film, Viridiana, had any Spanish identity, despite the fact that it was Buñuel’s first feature to be shot in his native country and even had two Spanish producers. (After it won the Golden Palm at Cannes, causing a scandal, all of the papers identifying Viridiana as a Spanish feature were destroyed by the Franco government, so that by the time it was banned in its entirety by the Spanish censor, it was listed solely as a Mexican production.)

Ever since I first saw The Young One, in Paris in the late 60s, I’ve never been able to accept this apparent public consensus about consigning it to oblivion. The film has indeed been all but written out of film history, having been accorded scant attention in most studies of Buñuel and even less notice elsewhere. Even today, very few people seem aware that it exists. At the same time, it’s impossible to imagine a time when such a movie could ever become fashionable. Apparently simple, it’s riddled with dark ironies and subtle ambiguities, and the Surrealist high jinks that were Buñuel’s calling card at the very beginning and end of his career — most often figuring as signature interludes in his Mexican pictures–are nowhere in evidence.

Paradoxically, even though it’s technically a Mexican coproduction and was shot in its entirety in Mexico — near Acapulco and in Mexico City’s Churubusco Studios — and not in South Carolina, as has sometimes been misreported, The Young One is in some ways almost as American as Viridiana is quintessentially Spanish. In fact, speaking now as an American southerner who grew up in Alabama, I would argue that Buñuel’s unsung masterpiece is one of the most authentic and pungent of all the films set in the American South. In this respect, it even compares favorably to Jean Renoir’s far more prestigious The Southerner (1945) — which also stars Zachary Scott and even had some dialogue scripted by William Faulkner. As James Agee, another disgruntled Southerner, wrote of the Renoir film, “Most of the people [in the film] were screechingly, unbearably wrong. They didn’t walk right, stand right, eat right, sound right, or look right.” And, with the possible exception of the only non-American in the cast, Claudio Brook, very little of this criticism could be leveled against The Young One.

But although the film never fundamentally betrays Buñuel’s leftist convictions in any way, it confounds so many workaday rules of political correctness — left and right, then and now — that no one could ever see it as any sort of tract. One of his most sensual, sheerly physical works, it never qualifies as either pornography or sensationalism (though it was probably marketed originally as both), and its black comedy has a moral complexity typical of his finest work. The film refuses to label any of its five characters as either a hero or a villain. To quote Buñuel again, “This refusal of Manichaeism was probably the major reason for the film’s commercial failure.”

It’s worth bearing in mind too that The Young One was made a full decade after Buñuel’s Los olvidados (The Young and the Damned) and only a year before Viridiana, the film that launched his highly successful “second” career as a mainly European director; It came at the tail end of a long period of low-budget Mexican pictures, most of which received very little international notice. In other words, it lacked a market in 1960, despite the racial and Lolita themes, because Buñuel still hadn’t become a “brand name” director, a recognized auteur.

***

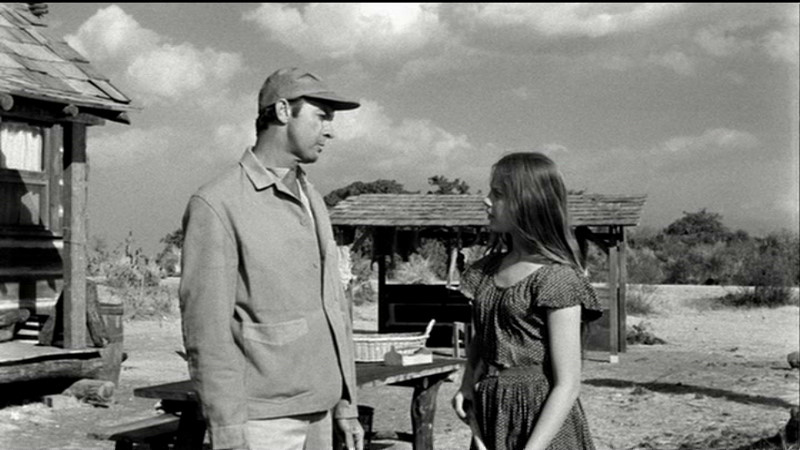

Over the strains of Leon Bibb singing “Sinner Man” — the only sound-track music we hear in the film, heard over both the beginning and the final sequence — a black jazz clarinetist named Traver (Bernie Hamilton), fleeing for his life, arrives in a stolen boat at a game-preserve island off the Carolina coast. Miller (Zachary Scott), the game warden, kills a rabbit and brings it home to his shack, where he finds that his alcoholic handyman Pee-Wee has just died. Pee-Wee’s orphaned teenage granddaughter Evvie (Key Meersman) is putting on the dead man’s boots in the adjacent cabin and sniffling when Miller arrives, but he’s hardly affected. They cursorily bury Pee-Wee in the backyard; Evvie wants to bury his liquor bottle too until she gets Miller sharply reprimanded her for “wasting bad whiskey.”

In the morning, after Miller takes his boat into town, Evvie encounters Traver while tending to the beehives. Ravenous, he takes some honey and an apple from her but then pays her $20 for one of Miller’s shotguns and some of his canned goods. They establish a wary friendship, and after Traver accidentally causes a leak in his boat with the shotgun, she supplies him with tools to repair it. When Miller returns that day and discovers that a black man has taken some of his things, he promptly chases after Traver, tries to kill him, and shoots several more holes in his boat.

Several other tense confrontations and power shifts between Traver and Miller follow, complicated by the presence of Evvie; the object of Miller’s growing lust and Traver’s casual ally, she’s innocent of sexuality and racism alike. (And unlike Lolita’s, her own innocence can’t be taken for flirtatiousness.) After Traver agrees to work temporarily as a handyman for Miller in return for board while he repairs the boat, he spends the night in Pee-Wee’s cabin, causing Evvie to move to Miller’s shack and thereby enabling Miller to consummate his lustful designs on her. Things are complicated still further by the arrival from town of a Protestant preacher (Claudio Brook) and Miller’s boatman Jackson (Crahan Denton), who discover at about the same time that Traver is fleeing from a rape charge and that Miller raped Evvie the night before.

The symmetrical balance of these two virtually simultaneous discoveries is a crucial factor in the overall moral relativity of Hugo Butler and Buñuel’s screenplay. The complex moral and practical tradeoffs that ensue are too labyrinthine to recount fully here, but it should be stressed that they’re at the heart of the movie. In fact, the film basically consists of nothing but intricate transactions and exchanges — of goods, money, services, gifts, promises, favors, epithets, injuries, and loyalties. In the final analysis, Buñuel refuses to condemn or exonerate anyone; to suggest only part of the film’s audacity, he shows that the smitten child abuser overcomes some of his racism once becomes a potential fugitive from justice, and one of his motives is clearly wanting to win back Evvie’s respect. Traver — the only urban sophisticate in the movie, in contrast to the primitive rural feudalism of the other four — winds up sparing Jackson’s life in order to avoid another excuse for a lynching, but he’s hardly idealized himself: in one scene, trading army anecdotes about World War 2 experiences as well as racial insults with Miller, he’s made to seem almost as childish as his persecutor. And this in turn complicates the degree to which both men might be viewed as competing father figures in relation to Evvie — though pointedly not as competing rapists. (Traver – whom we and the preacher eventually realize is entirely innocent of the charges of rape brought against him by an alcoholic white woman — also never shows the slightest bit of sexual interest in Evvie.)

Jackson, who never ceases to be a monstrous bigot, isn’t judged unequivocally either, even if he comes closer to figuring as a villain than anyone else; Buñuel clearly sees him as a crude, pathetic moron but also as the product of his conditioning, not simply as evil. By the same token, Buñuel appreciates but never patronizes Evvie’s “uncivilized” innocence, and we’re actually persuaded to wonder whether the preacher will have much more of a beneficial effect on her than Miller does. When we briefly see her near the end, just before leaving in a boat for the town on the mainland, playing hopscotch in her hobbling high heels (a present from Miller), we’re led to ponder what price her “civilizing” at the hands of either man is likely to have. In many respects, she’s an earlier draft (and a somewhat younger version) ofthe daughter of the servant Ramona in Viridiana, but her relative innocence and purity also makes her somewhat akin to Viridiana herself.

As for the preacher, he’s shown as principled, pious, sincere, and overtly nonracist, but that doesn’t prevent him from choosing to flip Traver’s mattress before he’ll sleep on it himself. On this occasion, however, Buñuel uncharacteristically restrains himself from ridiculing the devoutness of this man in all other respects, and one might also note that he ultimately serves as a much better and certainly more compassionate father figure for Evvie than either of the two main male protagonists.

Although this preacher is the only overly religious figure in the film, it’s important to acknowledge that, this being a work by Buñuel, it’s a film informed by religion in numerous ways, most of them far more subtle. The Leon Bibb folk song, “Sinner Man,” already establishes a religious contextbehind the opening credits — and it’s worth adding that the fact that it’s a song about a man on the run, sung by a black man, establishes a certain rapport with Traver’s viewpoint before any other character enters the picture. (Later on, we also get some camera angles corresponding to his point of view.) Furthermore, when he subsequently tells Evvie that she looks like an “angel of mercy,” this helps to establish the role that she’ll play for him throughout the story.

A few words on the script, cinematography, and casting. The film is very loosely inspired by a 1957 Peter Matthiessen story, “Travelin Man,” that’s radically different in most particulars, apart from the swampy setting and its predatory inhabitants, which are rendered in detail. (Traver in the original is an escaped convict and an arsonist who loves to fight — a much tougher customer, and neither a musician nor a Northerner — and he winds up getting killed at the end by an unnamed white man who corresponds roughly to Miller, whom he’s just clubbed; no other characters appear in the story.) The script is credited to “H.B. Addis” and Buñuel. The former is the pseudonym of Hugo Butler (1914-1968), a talented blacklisted screenwriter who moved to Mexico in 1951 and was reportedly fluent in Spanish, thus making him an ideal collaborator for Buñuel (although Buñuel himself had previously lived for some time in both New York and Los Angeles and was probably fluent in English); “Addis” was the brand of a pencil he used. The following year, under another blacklist pseudonym, Philip Ansell Roll, Butler coscripted Buñuel’s only other film in English, the equally neglected Adventures of Robinson Crusoe. His fascinating filmography also includes MGM prestige pictures of the late 30s and early 40s (A Christmas Carol, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn,Young Tom Edison, Lassie Come Home), Jean Renoir’s aforementioned The Southerner, some of the best films of blacklisted directors John Berry (From This Day Forward, He Ran All the Way) and Joseph Losey (The Prowler, The Big Night, and Eva), several films of Robert Aldrich (World for Ransom and Autumn Leaves prior to The Young One, Sodom and Gomorrah and The Legend of Lylah Clare afterwards), and Frank Tashlin’s neglected and underrated first feature, The First Time.

The Young One’s cinematographer is the great Gabriel Figueroa, who shot most of Buñuel’s best Mexican work (including The Young and the Damned, El, Nazarin, and The Exterminating Angel). He can be credited for much of the film’s physical impact, although part of this can also clearly be ascribed to the richly textured and evocative soundtrack, which is particularly attentive to the noises of various kinds of wildlife on the island.

Aside from Meersman, the actors are all professionals: The Texas-born Zachary Scott (1914-1965), the best known of them, had already appeared in such Hollywood movies as The Southerner, Mildred Pierce, Ruthless, and Appointment in Honduras. He and his second wife, actress Ruth Ford, could be described as William Faulkner specialists at various periods because of their associations with The Southerner, various productions of Faulkner’s play Requiem for a Nun, and even Light in August (to which they owned the film rights). The less well-known Bernie Hamilton — who was the brother of jazz drummer Chico Hamilton, and passed away in December 2008 — is perhaps best known for his work in American TV and in Let No Man Write My Epitaph, The Devil at Four O’Clock, and One Potato, Two Potato. (He also has uncredited small roles in such varied films as Carmen Jones, Kismet, and Underworld U.S.A.) Claudio Brook — as previously noted, the only non-American in the cast — actually went on to become a Buñuel regular in Viridiana, The Exterminating Angel, Simon of the Desert, and The Milky Way. Despite the awkwardness of his slight Spanish accent, his Reverend Fleetwood is a memorable and effective creation, and his performing of Evvie’s baptism is priceless.

***

Approached superficially and ungenerously, The Young One might at first seem like a bad imitation of Tobacco Road; if one confuses its deceptive simplicity with simplemindedness, as some viewers have, it might even come across as camp. “How old are you?” Miller asks Evvie after noting that she’s starting to blossom physically. “I use t’know when Mom was alive, befo Gramps brot me out here,” Meersman replies, in a delivery so flat as to make her seem not so much a bad actress as a nonactress. (Buñuel reported having so many difficulties directing her that he almost closed down the production, but in fact Meersman’s vibrantly unpolished presence turns out to be one of the movie’s clearest and sturdiest triumphs.) “You know,” Miller says, preparing to grasp her thigh, “they tell the age of a horse by his teeth, but with a woman or a hawg, it’s flesh and weight that counts.”

Many reviewers in 1960 alluded to Tennessee Williams, but apart from the southern setting, they couldn’t have been further from the mark. A much more probable literary source is William Faulkner, whom Buñuel on other occasions showed some interest in adapting. In fact Evvie registers at times as a younger, less idealized Lena Grove from Light in August (one of the novels Buñuel showed interest in adapting, along with As I Lay Dying) – an innocent, semi-mindless character who knows precisely who she is and remains whol1y secure in her identity as long as she remains on the island, unlike all the existentially unfocused and perpetually bargaining male `actors’ surrounding her. (Meersman’s lack of guile, actorly and otherwise, also intermittently suggests a more glamorous version of Robert Bresson’s Mouchette as she goes about her daily chores.) Miller and Jackson’s casual meanness and the preacher’s square sincerity, both observed with ironic wit, also suggest Faulkner, but at the same time they’re quintessentially Buñuelian, revealing a humorously dispassionate view of human behavior and its contradictions.

The island itself — where all the action, apart from a brief early flashback, transpires — is a palpable, living presence with its swarming and chattering insects and varied plant and animal life, a character in its own right, closely identified with Evvie. Buñuel establishes this universe as elemental and predatory from the outset: a few into the film Traver has eaten a live crab and Miller has shot a rabbit, and these men are far from the only predators; not long afterward, Evvie knowingly steps on a tarantula, and we see a badger eating a chicken. But the natural world, like the characters, is never presented formulaically: Buñuel looks at everything with the amused curiosity of an entomologist or anthropologist, though the society and world he examines are not fundamentally different from our own.

Jonathan ROSENBAUM

first published in:

www.tiny.cc/6jdzhz