Lucidno

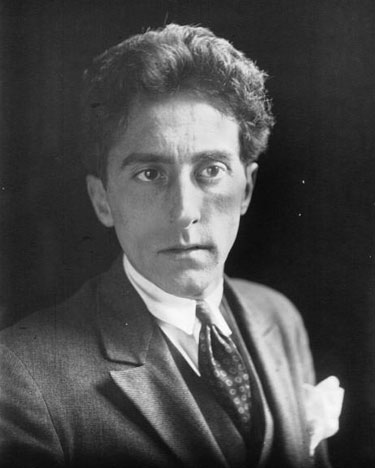

Interview: Ivan Passer

|

To a certain degree, the Karlovy Vary International film festival was an ideal place to interview Ivan Passer. Held annually in July in the pretty Czech Republic spa town (formerly Karlsbad), the festival was established in its present form in 1965, the same year that Passer’s only Czech feature, Intimate Lighting, was first shown to the public. Passer was invited to Karlovy Vary to introduce the world premiere of the digitally restored Intimate Lighting, undertaken by the leading Czech studio UPP and sound studio Soundsquare. It was a pleasure to watch the newly-minted copy on the big screen of this protominimalist masterpiece in which people eat, drink, play music and reminisce. Its gently mocking humor and keen eye for the minutiae of human behavior, got me wondering if Jim Jarmusch, whose Patterson I had watched the day before, had been directly or indirectly influenced by it. Ivan Passer was one of the new wave of Czech film directors who emerged in the mid-60s during the short-lived social and cultural democratization in Czechoslovakia, which afforded filmmakers unprecedented artistic freedom. With his childhood friend Milos Forman, Passer co-wrote Loves of A Blonde, 1965) and The Firemen’s Ball (1967). In that period, Passer, Forman, Vera Chytilova, Jiri Menzel and Jan Nemec, among others, made films that rejected the official state socialist-realist aesthetic and produced eclectic, highly assured features that captured the world’s attention. After their films were banned, and having fled the Russian tanks in 1968, with Forman, Passer, in exile in the USA, made two masterpieces, Born to Win (1971), one of the most sensitive and realistic films on drugs, and Cutter’s Way (1981), one of the best film noir of the ‘80s. I met Passer in a lounge of the opulent neo-Baroque Grandhotel Pupp, a setting completely at odds with Passer’s relaxed, unassuming, witty personality. On the verge of his 83rd birthday, Passer, who looks at the world with a certain quizzical smile, is still Camera Lucida: What did you think of the new print of Intimate Lighting? I. Passer: They did a brilliant job. I wish I could have worked with black and white more. It’s easier to control the image. Color is much more difficult to get the effect you want. Incidentally, did you know that there is no blue in Cutter’s Way? I and Jordan Cronanweth, the wonderful cinematographer, decided it would create a better atmosphere. A black and white film in color. Camera Lucida: I notice that after 48 years in the USA you still don’t have an American accent and you haven’t forgotten your Czech. I. Passer: That’s one of the things I miss most about living in California. I don’t get to speak my own language. Camera Lucida: Why have you never returned to your homeland to make a film like your friend and compatriot Milos Forman? I. Passer: I would have been arrested during the Communist period before the Velvet Revolution in 1989. They allowed Milos to make Amadeus in Prague in 1984 because he was more internationally famous than me. However, a few years ago, I tried to set up a film of the Masin brothers, Josef and Ctirad, known for their armed resistance against the communist regime in Czechoslovakia in the 1950s, but there was reaction against it in the Czech Republic, because during the brothers’ raid on a police station, a policeman was killed. Camera Lucida: It seems inconceivable that Intimate Lighting, an almost plotless comedy, about the everyday pleasures of life, should have been banned for 20 years. Can you explain it? I. Passer: I believe that the Party was worried when they saw ordinary people, with all their weaknesses and strengths, depicted on screen. I think they also preferred to be attacked directly than to be ignored completely. Before the clamp down, Milos and I got together to discuss how in this God-forsaken country we could make good movies. We took a piece of paper and we wrote down several points like “it should be a comedy” because the Communist Party and the censorship were more tolerant with comedies. “It should be shot outside of the studio, in the streets” because they would not look over our shoulder that much. “We will use non actors” and “We will use natural light.” My first film, using these precepts, was a 20-minute short, A Boring Afternoon (1964), about all the things that happen when, ostensibly, nothing is happening. Miroslav Ondricek, who shot it, was a soccer fan. He believed that his filming a number of matches made him more able to work with non-actors who could not be expected to hit their marks for lighting. When casting Intimate Lighting, which was about a group of friends who play music together, I had to decide whether to have actors pretending to play instruments, or musicians who I could get to act. I settled for non-actors. We were at a music school, and I literally grabbed the principal in the corridor and asked him if he would play the lead of the cellist. At first he didn’t want to do it, but after he read the script, he said ‘it’s about me.’ |

Camera Lucida: How did Born to Win, your first American film, come about? I. Passer: I didn’t think I could ever make films in the USA. My English was poor. After a couple of years trying to survive in New York, I met a theatre director and writer David Milton at a birthday party. He invited me to his play off-off Broadway. There were only four people in the audience. Afterwards we had a beer and discussed writing a screenplay. Three months later we had a script. Not thinking it would come to anything, I said I would direct it. Some months later, I had forgotten about it, when United Artists bought it for George Segal who owed them a few films on his contract. I didn’t know anything about drugs, so I learned a lot of new things, did research. It interested me because here in the country of freedom – for me who came from a country of restricted freedom – there are these people who voluntarily give their freedom away, and are enslaved by drugs. That fascinated me. Anyway, I thought to myself, it’s easy to make films in the US. Later I found out the opposite. Camera Lucida: Did you have problems with producers? I. Passer. Not really. Remember that I had lived under a Stalinist regime, so I knew how to deal with little Stalins in America. I generally got what I wanted. I tried to stick to my own team as much as possible. I often got my own way in casting. For example, I gave Robert de Niro and Burt Young their first breaks in Born To Win. For Cutter’s Way, U.A. wanted Richard Dreyfuss to play the horribly crippled Vietnam vet Cutter. I thought they were wrong. Anyway, I went to see Dreyfuss in Othello in Shakespeare in the Park. The noisy audience were not paying much attention. Lying on the grass making love and smoking drugs. Suddenly an actor came on the stage and quietened the audience with his voice. It was John Heard as Cassio. I managed to convince UA that he was right for the role. We were also lucky to get Jeff Bridges who had just come off the long shoot of Heaven’s Gate. Camera Lucida: Which of your films are you proudest of? I. Passer: I don’t have a favorite. I like Born To Win, but I think its blend of European and American sensibilities, disoriented many critics at the time. It’s now considered one of my best films. Maybe Cutter’s Way, which is perhaps my most American film. It is a damaging account of a nation that has lost its final illusions in the Vietnam War and of a Camera Lucida: Any films you regret making? I. Passer: Not really. Although I made a mistake in the ending of Law and Disorder (1974), my second US film, with Carroll O’Connor and Ernest Borgnine as vigilantes. It suffered from a sudden shift of tone towards the end. The audience was laughing all the time, suddenly this guy was killed and the audience was stunned. I learned that you should never do that. Camera Lucida: Your last film credited to you was in 2004, Nomad: The Warrior, an epic set in 18th-century Kazakhstan. You’re given a co-director credit. What happened on that? I. Passer: It was shot on location in Kazakhstan in English. We kept getting instructions from on high which I imagined came from the authoritarian regime. The government had invested $40 million in the movie production, making it the most expensive Kazakh film ever made. They wanted the film made for prestige reasons, but on their own terms. For example, I found a beautiful 18-year-old Kazakh girl for the leading female role. However, a message came to me that she was not suitable because she had “no breasts”. Apparently, Kazakh warrior women had large breasts, sometimes cutting one off to make it easier to carry rifles. Unfortunately, due to financial and weather problems the film shut down halfway through. It was then bought by the producer brothers Bob Weinstein and Harvey Weinstein, who replaced me with Sergey Bodrov, and released it the following year. Bodrov very kindly said that he had taken the job to protect the work I had already done. Camera Lucida: Why haven’t you made a film since? I. Passer: I refuse to do violent films. I consider it is dangerous. I have seen real violence during WW2. Violence affects some people who are not able to realise the difference between reality and fantasy. So I take myself out of 80% of the American market. I got offers all the time and I rejected them. I don’t want to see these movies, how should I make them? I also have no desire to shoot on digital. Camera Lucida: Have you any projects in the pipe line? I. Passer: I’ve had a few meetings with Dustin Hoffman on a project called Viagra Falls. There are others, but I think that money plays a much bigger role than ever before, mainly in choosing innovative scripts. Ronald BERGAN

|

Classical music in film

Classical music in film