In Memoriam

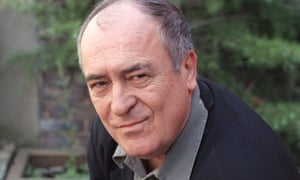

Bernardo Bertolucci obituary

Having already made a reputation as one of the greatest Italian film directors of his generation, Bernardo Bertolucci, who has died aged 77, gained worldwide notoriety with Last Tango in Paris (1972), mainly as a result of its explicit sex scenes. In his depiction of the painful, loveless, joyless relationship between a middle-aged American man (Marlon Brando) and a young Frenchwoman (Maria Schneider), Bertolucci set out to show, he said, that “every sexual relationship is condemned”.

Fifteen years later, Bertolucci gained his greatest international triumph with The Last Emperor (1987), which won nine Oscars. According to Bertolucci, cinema is “a truly poetic language”, a claim that many of his films justify. He had started out as a poet, with his collection In Cerca del Mistero (In Search of Mystery) winning the Viareggio prize in 1962, as his father had done before him.

He was the son of Attilio Bertolucci, a well-known Italian poet, and Ninetta (nee Giovanardi), a school teacher. As a boy Bernardo often accompanied his father to the cinema in Parma, the city where he was born and brought up, and began making 16mm films when he was 16 years old. He got to know the poet Pier Paolo Pasolini through his father, and when Pasolini made his first film, Accatone (1961), Bernardo was hired as production assistant.

Before the Revolution (1964), a far more personal film, explores the problems of a selfish middle-class young man who is torn between radical politics and conformity, and between a passionate affair with his young aunt and bourgeois marriage. He opts for respectability on both counts. The film, loosely based on Stendhal’s The Charterhouse of Parma, is technically impressive, as is Bertolucci’s ability to articulate themes, such as the betrayal of a totemic father and the connection of the libido with politics, that would mature in his later work. However, as with the film’s hero, there is an element of the dilettante in Bertolucci’s approach.A year later he directed his first feature, The Grim Reaper (La Commare Secca), based on a five-page story outline by Pasolini. It told of an investigation into the murder of a prostitute in Rome, seen from different perspectives of different people on the events of her last day. Each episode, as told to the unseen investigator, was filmed in a different style. It is, as the director admitted, the film of “someone who had never shot one foot of 35mm before but who had seen lots and lots of films”.

This impression grew stronger in Partner (1968), which is an undigested homage to Jean-Luc Godard, about a young man literally divided into two by having a double. Derived from Dostoevsky’s short novel The Double, and updated to the Rome of 1968, it has the central character, played by Pierre Clémenti, speaking French while all the rest speak Italian. In the same year, Bertolucci was credited with the story of Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in the West.

Bertolucci’s reputation was greatly enhanced when he joined forces with the cinematographer Vittorio Storaro, who had been a camera operator on Before the Revolution. The Spider’s Stratagem (1970), the first of eight films they made together as director and director of photography, easily transposed the Jorge Luis Borges story Theme of the Traitor and the Hero from Ireland to Italy. As oedipal and labyrinthine as its source, it concerns a young man who revisits the village in the Po valley where his father was murdered by the fascists in 1936, and gradually discovers that his father, whom he had considered a hero, was really a traitor.

The Conformist (1970) most successfully brings together Bertolucci’s Freudian and political preoccupations in an ironic study of pre-war Italy (beautifully captured by Storaro) and an attempt to penetrate the mind of ordinary fascism. The childhood trauma of having shot a chauffeur who tried to seduce him, together with his own repressed homosexuality, is a strong factor in making Marcello (Jean-Louis Trintignant) contract a bourgeois marriage and offer his services to the fascist party, for whom he is asked to assassinate his former professor. The Conformist saw the full flowering of Bertolucci’s flamboyant style – elaborate tracking shots, baroque camera angles, opulent colour effects, ornate décor and the intricate play of light and shadow that give his work such a distinctive surface.

Photograph: Allstar/Cinetext

After the release of Last Tango in Paris in Europe, Bertolucci was indicted by a court in Bologna for making a pornographic film. Although he was acquitted, he lost his civil rights (including his right to vote) for five years and the Italian courts ordered that all copies of the film should be destroyed. In recent years, further controversy surrounded the extent to which Schneider had consented to elements of the film shoot.

The worldwide acclaim and box office for Last Tango in Paris helped Bertolucci obtain the vast financial resources needed to embark on the long-planned project 1900. With this $6m, five-hour epic, released in 1977, Bertolucci turned away from the introspection of his previous films and tried to make a popular movie of the class struggle using the style of both American epics and the socialist realism of the Russian cinema of the 30s. Italian history is seen through the diverging lives of Olmo (Gérard Depardieu), the son of a peasant woman, and Alfredo (Robert De Niro), the son of the lord of the manor (Burt Lancaster), both born on the same day, 27 January 1901, through to Italy’s Liberation Day, 25 April 1945. Often bombastic and didactic, it enters greatness in the last 30 minutes.

Luna (1979) was the story of a passionate mother/son relationship, in which an internationally renowned opera singer (Jill Clayburgh) has an almost incestuous relationship with her spoiled teenage son who is searching for a father. Bertolucci’s virtuosity is undeniable in the film, which threads together a series of splendid scenes (or arias and duets) on the string of an opaque plot.

The Tragedy of a Ridiculous Man (1981) was Bertolucci’s first film to deal with contemporary Italy since 1964. The elliptical, quasi-thriller tells of a factory owner and self-made man (Ugo Tognazzi), who sees his son being forcibly hustled into a car. The police suspect the victim of colluding in his own kidnapping because of his far left sympathies. The reverse of the Spider’s Stratagem, in which a son investigates his father’s life, this ambiguous view of terrorism failed to please the public and critics mainly because the crime is not solved.

It was six years before Bertolucci was able to make another film. In the meantime, he wrote two screenplays based on Dashiell Hammett’s Red Harvest, which he hoped would be his first film set in America. When nothing came of it, he went to China to shoot The Last Emperor in English. It was the first western film to be made almost entirely in China with active official Chinese participation. The biopic of Pu Yi, China’s last emperor or “Son of Heaven” who is “re-educated” by the Maoist regime, is a fascinating, sumptuous epic, covering nearly 60 years of China’s cataclysmic history.

Another exploration of the Bertolucci theme of the upper classes learning about working-class life, the film looks every cent of its $21m cost, which included paying for 19,000 extras, 9,000 costumes, and 2,000 kilos of pasta for the Italian crew. Especially impressive was Storaro’s luminous photography, capturing the golden splendour of the palace in the Forbidden City.

After his two-year sojourn in China, Bertolucci completed what he called his “eastern trilogy”, his exploration of non-western cultures, which opened up his work to existential and philosophical themes: The Sheltering Sky (1990), shot in Algeria, Morocco and Niger, and Little Buddha (1993), shot in Bhutan and Nepal.

The former, based on Paul Bowles’ mystical, metaphysical semi-autobiographical novel, followed an egocentric American couple travelling to find the meaning in their relationship. Bertolucci felt that The Sheltering Sky had much in common with Last Tango in Paris. “Isn’t the empty flat of Last Tango a kind of desert and isn’t the desert an empty flat?” he asked. But despite the beautifully captured arid landscapes, the film itself was dramatically arid.

Little Buddha sets the ancient tale of Siddartha (Keanu Reeves) and his quest for enlightenment alongside a contemporary story of an eight-year-old American boy who may be the reincarnation of a famous Buddhist master. The film, which contrasts the two worlds by underlining the blue tonality of Seattle and the red and gold of the oriental story, was aimed at children, though it was more simplistic than simple, and pleased neither children nor adults.

After his expensive, exotic enterprises, Bertolucci returned to home ground, working on a smaller, more intimate scale with Stealing Beauty (1996), a minor piece about a teenage American girl’s sexual awakening at a villa in Tuscany, inhabited by artists and bohemians, and Besieged (1998), set in Rome, which focuses on the relationship between a reclusive English pianist and his young African housekeeper. Made originally for Italian television, Besieged gave Bertolucci a chance to rediscover a kind of spontaneity in film-making which he felt he had lost since the 1960s.

Bertolucci then tried to recapture the spirit of the student uprising in Paris in 1968 in The Dreamers (2003), but its events provide only a background to a cloistered ménage-a-trois whose main preoccupations are sex and the movies. Paying homage to Jean Cocteau’s Les Enfants Terribles, the film is the apotheosis of Bertolucci’s cinephilia, always an element in his films.

Owing to serious back problems, he used a wheelchair and did not make another film for nine years. Me and You (2012), his first Italian movie since 1981, was a relatively modest affair with a small cast and largely one location – a cellar in which a teenage boy is holed up with his half-sister.

Bertolucci is survived by his second wife, the screenwriter and director Clare Peploe, whom he married in 1978. His first marriage, to the actor Adriana Asti, the female lead in Before the Revolution, ended in divorce.

Ronald BERGAN

first published in

www.theguardian.com/film/2018/nov/26/bernardo-bertolucci-obituary