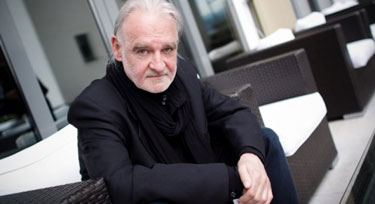

Interview Béla Tarr

| BT:Yes, of course. Before I started doing this job, I was always surrounded with people. It is a question of social awareness.

You have to know that, when you make a film, you must have money. And making a film costs a lot of money. Money comes from people, you spend the money of tax payers, money obtained from payments of various taxes... so, since I spend precisely that money when making a film, it is my duty to show to people what I see in ordinary life. And life, as you know, cannot exactly be called an „ordinary phenomenon"... everyone has their own ordinary life, and everyone has only one life... What is the quality of that life, how people cope in their life, what kind of pitfalls they fall into, what chance they have to experience joy... are the kind of things that interest me, questions I like to deal with. CL: Where does the title The Turin Horse come from? A direct relationship doesn't actually exist... maybe it's a stupid question... BT: It is not a stupid question.... The answer to that question comes from Mr. Nietzsche directly. He was the one who met the horse in Turin and he is the one who created the Übermensch theory. We all know what he claimed: God is dead, everything now depends on people and on Übermensch, the superman, that is, who is greater than God. As God is dead, it looks pretty easy... But... The man who created an ideology according to which the entire strength lies in a human being, walking in the street, met a horse who was abused – and the whole theory fell apart. And he said, all right, enough with this, and protected the horse with his body, then broke apart, and for the next ten years, to his death, didn't say a word... This is a well-known story about Friedrich Nietzsche and divergences concerning theories and ideologies, but... nobody, up to now, has asked a question whatever happened to the horse. Precisely this was the question which haunted me, my friends and colleagues. One could say that the screenplay itself was written very fast, but it took a long time for it to become what it is. In fact, it was a long writing process... The essential question „what happened to the horse?" was asked by the screenplay writer Laszlo Krasznahorkai.... at the beginning of the 1980's, and I have been thinking about it intensively since 1985. From time to time, between two films, we'd talk about it, and the question would resurface again. When we stopped the shooting of The Man from London (at that time I was in a terrible mood), Laszlo came up to me and suggested that we think and discuss the „horse question". We started talking about what could be done with „that horse", got into some big arguments, and he, visibly upset, simply ran away, only to send me two days later a text which was wonderful... and that's it. We decided to try to realise it. CL: This is a very simple question, but such are the issues you, generally, deal with: love, hatred, sadness, poverty... these are the most powerful topics of any film, but they are also the most crucial life topics... BT: When you read the Old Testament, you can find in it all of this. That is why I thought that we didn't need stories anymore. They have already been told and written. We, time and again, tell the same old stories. There is no need to invent new ones. {niftybox background=#8FBC8F, width=360px}But what we could and what we should show is the way in which we tell these old stories again and again, to show the way in which we repeat these old stories.{/niftybox}

Of course, we are all different, each one of us has his/her own, different life, and each one of us has his/her own freedom... what matters to me is what people do now, at this very moment... I am still interested in that, but I don't make films any longer... CL: Does the whole concept of existentialism revolve around the idea that we should eventually surrender to our surroundings? Is that the message of your film? BT: That is a very sophisticated question, but, if you remember, Milan Kundera wrote a novel entitled The Unbearable Lightness of Being. We just wanted to show you what „the unbearable heaviness of being" is like. You know, with each day, life becomes shorter and shorter, which is terrifying. For I don't know how long I have been thinking about it, but also about the ways in which I could talk about it; how to explain what is happening with that fucking death, which is coming, which is here, right in front of us... how to speak about these things... |

Someone said that this was a film about apocalypse. No, because the apocalypse is a huge and grandiose event, which looks like a TV show. I just wanted to show how life is, day by day, becoming more and more helpless, until one day it just vanishes. That's all. CL: The whole object on which the film is shot had been constructed. Why? BT: This is a very serious question, although it may not sound like that. I am talking about a crucial thing. When you shoot a film, you have to know that the location is one of your „protagonists" and that it has a face, just like actors have one, that the location has a soul and that it's highly important. That's why I am very careful in my search for locations when shooting a film. I treat music in a similar way. I always want to know before the shoot what music my film will have. Because it is one of my protagonists. That's why I need to know when the music will be heard, and when not, because I need to know what I hear, and what you will hear at that moment. When you make a film, you have to take care of everything, it's very important. Of course, I need to know what the film will look like, from the first to the last frame. CL: You have been working with the same team for years. They are like a family, sound engineers, cameramen, writers... BT: I have also been working with Agnes, too, my editor, who has also been my wife for 27 years... my team is made up of people who are my friends, because I hate to explain anything about the filming itself. I like to go on set and say to them: „OK, this is an intro scene, then we move positions...then comes that, that and that...let's try to do just that". This is very simple. So that is one of the reasons. The second reason is that all angles of seeing things are similar. We don't need to talk about art. We talk about life and what is happening around us.You know, it's very nice to talk about you children, your daughter or whatever... {niftybox background=#8FBC8F, width=360px}The situation we are in is very serious. To talk about art is very dangerous. Don't do it if you are making a film. Only listen to living people...{/niftybox}

I would like to thank you for your attention and to express great gratitude for coming to watch all this shit that we filmed during 34 years. As far as I am concerned, I will now take a break. CL: Why? BT: Everyone knows that. Really, I am done with it. CL: I suppose you mean that you've said it all... BT: Exactly, I have said it all. Béla Tarr said, according to eyewitnesses, that he'd return to the cinema to say hello to the projectionist, who must have been the only one, he was sure, who saw the film to the end. And to apologise to him because his last movie wasn't shorter. He was greeted by a packed Arena Cineplex cinema and an enthusiastic audience, eager to talk.

|