Lucidno

| Let us return to La Pivellina. How does it place its spectator, and what is the politics of that placing? In a nutshell, it is a movie, in this mode of Aumont's cinema of encounter, which not only touchingly and tearingly dramatises the biopolitical problems of social identity and status. More (and more deeply) than that, it completely draws us into the processes of naming, identifying, recognising, attributing status to characters, situations, gestures, events. When you don't know where you are as a spectator – when you suddenly do not have the crutch of a backstory, or the usual ongoing elaborations and narrations – you don't really know who or what anything is, forming and deforming on screen before you.

{niftybox background=#afdeb2, width=360px}In that process – in which you, too, as a spectator, are a subject-in-process, as much as those within the film – you have to work particularly hard, sometimes in a vertiginous spin, to make sense of the relationships in the film (family relationships, social relationships, intimate relationships). Because all these relationships are, in the way they are presented, mysterious and open.{/niftybox} Patti could be, in a sense, Aia's aunt, or mother, or sister, or best friend; Patti's male friend could be her boss, or her collaborator, or her husband. All these are possible relationships; and the possibility, the openness, the flux of relations and identifications, is itself radical – and radicalising. (This is also the core of a very different but equally exciting film, Abbas Kiarostami's Certified Copy [2010].) That is why I think La Pivellina is a long way from the cinematic realism or naturalism with which even sympathetic critics have already tagged it, and thus closed it down. This idea of an ongoing and ever-shifting openness in a cinema of encounter would be one of the most intense dreams or wishes of one kind of political cinema – a cinema I believe we need more of today. In particular, as a part of its open process, La Pivellina sets up a kind of constant jamming, confronting mechanism: your usual projections, completely stereotypical and ideological in nature – the baggage you came in with as a spectator – can come undone, or at the very least get confused: this mature woman with her crazy bright red hair is an emblem of just such an undoing, which starts small (in this tiny detail) but quickly spreads like a viral contamination throughout every detail of the movie. This puts you as spectator, in your open place, at the polar opposite to those earmarked in the film – cops, doctors, professionals and social workers of every kind (a familiar trope of the Pialat/Cassavetes cinema of encounter). These are the law-and-regulation-wielding citizens who savagely stereotype, label and coercively, even brutally reduce, fix and act upon those figures we are still coming to know on-screen in a flux of mystery and uncertainty. I am drawn to a moment, or a memory, from Kaurismäki and The Man Without a Past. |

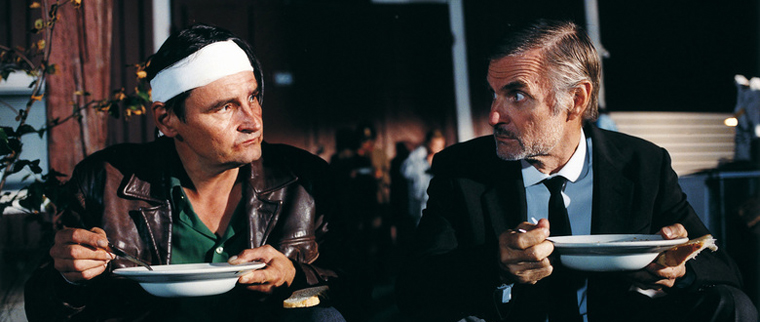

When I come back to that film not just with the eyes of a biopolitical allegorical interpreter – when I try to stay alive to the odd, often surreal details of its moment-to-moment unfolding – then the politics of the film, its mesh of the small, intimate personal love story with the issues of class, money and social identity, suddenly becomes much more powerful, and affecting – infectious, in fact. When it comes to the central love story between M and a Salvation Army worker named Irma (Kati Outinen) – who is absolutely nothing like the usual closed-down social worker figure I have just evoked – Kaurismaki's manner of showing it is typically chaste: we see no more than a kiss, yet another walk together, a holding of hands. But what emotion flows from this fragile, endangered union of lost, damaged souls, in this terribly uncertain and precarious social world!

Kaurismäki takes us right into the heart of the momentous transformations that can occur – not so much in the large-scale movements of story and character interaction or confrontation, but in the cinematic properties themselves: in the colours, shapes, objects, movements that figure a transformation. {niftybox background=#afdeb2, width=360px}In particular, I recall this from The Man Without A Past: simply a shot of this odd man and woman, standing there, obscured (in our vision of them), for quite a long time, by a passing, rumbling train. We see them and yet don't see them, grasp them and yet cannot grasp them; it is a wordless essay, condensed in a single shot, about social visibility and recognition, identity and identification. In this modestly magnificent moment, the cinema once again becomes a poetic and political love song.{/niftybox} NOTES 1. For a reading of the film along these lines but addressing a more global context, see Thomas Elsaesser, "Hitting Bottom: Aki Kaurismäki and the Abject Subject", Journal of Scandinavian Cinema, Vol. 1 No. 1 (2010), pp. 105-122. 2. Jacques Aumont, Le cinéma et la mise en scène (Paris: Armand Colin, 2006), pp. 170-171. 3. See the texts assembled in David Wilson (ed.), Cahiers du cinéma Volume 4, 1973-1978: History, Ideology, Cultural Struggle (London: Routledge, 2000). 4. See Serge Daney, "Falling Out of Love", Sight and Sound (July 1992), pp. 14-16. 5. Stephen Heath, Questions of Cinema (London: Macmillan, 1981). 6. See Slavoj Žižek, How to Read Lacan (London: Granta, 2006). This text was first delivered as a paper on a panel for the Society of Cinema and Media Studies (SCMS), New Orleans, 2011. Adrian Martin Adrian Martin is Adjunct Associate Professor in Media, Film and Journalism, Monash University. His most recent book is Mise en scène and Film Style (Palgrave, 2014) and he co-edits LOLA (www.lolajournal.com). In partnership with Cristina Álvarez López, he makes audiovisual essays for websites including MUBI Notebook, De Filmkrant, The Third Rail and Sight and Sound. |