Lucidno PARADJANOV

The Greatest Living Soviet Filmmaker

The following was published in the Chicago Reader on March 25, 1988. Criterion’s exquisite new edition of The Color of Pomegranates (see below)has prompted this reposting, even though a good many of the details, including the title, are now out of date. — J.R.

There are few people of genius in the cinema; look at Bresson, Mizoguchi, Dovzhenko, Paradjanov, Bunuel: not one of them could be confused with anyone else. An artist of that calibre follows one straight line, albeit at great cost; not without weakness or even, indeed, occasionally being farfetched; but always in the name of the one idea, the one conception. –- Andrei Tarkovsky, Sculpting in Time

After 15 years of enforced inactivity, the greatest living Soviet filmmaker is finally back at work again, but it’s astonishing how little we still know about him––about his art, his life, or even his name. You won’t find him in Ephraim Katz’s Film Encyclopedia or in the indexes of books by Pauline Kael, Stanley Kauffman, or John Simon (among others), and as far as I know, no one anywhere has ever written a book or monograph about him.

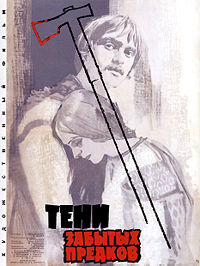

Roughly the first half of his oeuvre, made between 1958 and 1962, has never been exported. And part of the problem with his three staggering features since then––Shadows of Our Forgotten Ancestors, The Color of Pomegranates, and The Legend of Suram Fortress––is that they’ve reached us at the rate of one per decade, with such long stretches between them that each has effectively had to be considered in isolation from the others, without the benefit of mutual illumination.

Fortunately, Facets has fixed all that, and for the next week, all three of Sergei Paradjanov’s visionary masterpieces will be screened there nightly, in two separate auditoriums. While it won’t be possible to see all three in a single session, as I did recently––a singular if exhausting experience lasting a little over four hours––one can still see them, ideally in order, over two or three evenings, and to do so is to experience a certain revelation and clarification. The greatest art always creates its own context (”We impoverish ourselves by thinking only in film categories,” Paradjanov has said), and part of what has made his work seem more difficult, esoteric, and rarefied than it actually is has been the necessity of encountering it piecemeal. (Try to imagine what our perception of van Gogh might be like if we saw only one of his paintings once every ten years.)

For much too long, we’ve known Paradjanov mainly as a martyr of Soviet repression rather than as a working artist. Born to poor Armenian parents in Tbilisi, Georgia, in 1924 under the name Sarkis Paradjanian, he pursued dance, sculpture, and (in particular) vocal music before he attended film school in Moscow in 1946, where he studied with three filmmakers who are listed in Katz’s Encyclopedia: Sergei Eisenstein, Igor Savchenko, and Mikhail Romm.

Moving to Kiev in the early 50s, where he worked at the Dovzhenko Studios, Paradjanov made all his early films in Ukrainian, including Shadows of Our Forgotten Ancestors (1964)––the film that both created his international reputation and started his difficulties with Soviet authorities. Although the mystical pantheism and lyrical exuberance of Dovzhenko are often suggested in this tale of a rural woodsman in the Carpathians––there is even one ecstatic Dovzhenko-like shot with sunflowers to acknowledge the source––Paradjanov’s vision here is already uniquely his own. A mixture of paganism, ritual, poetry, and dance underlies that vision, and as Paradjanov pointed out, “We intentionally gave ourselves over to the material, its rhythm and style, so that literature, history, ethnography, and philosophy would fuse into a single cinematic image, a single act.”

When Paradjanov refused to dub Shadows into Russian, he was charged with Ukrainian nationalism––an ironic accusation considering his Armenian and Georgian roots; his candid opposition to studio bureaucracy and his expressions of solidarity with imprisoned Ukrainian intellectuals probably didn’t help, either. In any case, he wasn’t allowed to travel with his film to any of the numerous foreign film festivals that showed it, although it reportedly received 16 separate prizes.

Finally returning to Tbilisi after 19 years in Kiev, Paradjanov found all his subsequent film projects blocked until The Color of Pomegranates––his film about the celebrated 18th-century Armenian poet, musician, troubadour, folk philosopher, and archbishop Sayat Nova––came together in 1968. Shot in Yerevan, Armenia, the film benefited from a lot of local help from museums and the Armenian church, and though it was warmly received in Yerevan when it premiered there, it was termed “hermetic and obscure” in Moscow. When Paradjanov refused to re-edit it, it was shelved for two years, then given a limited run, but only after director Sergei Yutkevich recut it, eliminating about 20 minutes and adding explanatory intertitles. (This version, alas, is the only one visible in the U.S.––although Paradjanov’s cut is reportedly in distribution in England––and because it was exported surreptitiously, only poor, duped 16-millimeter prints have been available.)

Meanwhile, Paradjanov had moved back to Kiev and had several more film projects rejected. (Apparently the one that came closest to getting made was an adaptation of Hans Christian Andersen fairy tales for Soviet TV, scripted by the father of Russian Formalism, Viktor Shklovsky.) Then in December 1973, he was arrested on multiple charges, including homosexuality, homosexual coercion, anti-Soviet activities, illegal dealings in foreign currency and art objects, spreading venereal disease, selling pornography, and “incitement to suicide.” (Reportedly, the suicide of a young male friend in Paradjanov’s circle who had contracted a venereal disease accounted for more than half of these charges.) Accounts of the trial’s outcome vary considerably: According to Sight and Sound, Paradjanov’s outspoken self-defense, which included an admission that he was bisexual, led to his sentence of six years’ hard labor in a Ukrainian prison camp for homosexuality (”a criminal offense in the Soviet Union”), while all the other charges were dropped. According to Film Comment, homosexuality “in itself doesn’t constitute a criminal offense according to Soviet law,” and traffic in art objects was the only charge retained. According to Cinema-TV Digest, the three-day trial concentrated on the charges of homosexuality and pornography, and he was sentenced to eight years. (As indicated above, it’s remarkable how little we still know about this subject 14 years later––one indication of why much of the information here remains tentative.)

After an international protest, Paradjanov was released in 1978 and allowed to return to Tbilisi, but was still kept under police surveillance and forbidden to work. Apparently he was kept alive during this period by the efforts of friends and family, although some accounts also report that he was reduced to begging in the street. He was rearrested in 1982 on charges of attempting to bribe an official, then acquitted, and was finally able to make The Legend of Suram Fortress, with Georgian actor Dodo Abashidze as codirector, in 1984. Since then, he has made at least one additional short (in 1985), has shot a feature in a Turkish castle based on a Lermontov fairy tale, and is preparing to adapt the medieval epic The Lay of Igor’s Campaign for the Ukrainians. Last month he traveled to the Rotterdam film festival––where I was fortunate enough to see him, as well as his recent short (Arabesques Around a Pirosmani Theme). Thanks to glasnost, it appears that he’s finally coming into his own.

There’s certainly reason to feel anger about what Paradjanov has been through, but it probably would be myopic to assume that, apart from his imprisonment, he would have had an easier time of it elsewhere. (Significantly, in Rotterdam he was critical of Tarkovsky’s 1983 defection from the Soviet Union, arguing that both of Tarkovsky’s last films could have been made there.) Consider the late careers of certain equally intransigent gifted filmmakers elsewhere––Carl Dreyer in Denmark, Jacques Tati in France, Orson Welles in the U.S.––and the record is about the same, roughly one released film per decade, with no slackening of interest or effort on their part. (Welles did somewhat better, but only when his movies were financed in Europe or by himself; the last time a Hollywood studio backed him was over 30 years ago.)

Formally innovative regional artists are a rare breed, and the cultures they come from seldom seem to know how to relate to them. William Faulkner, perhaps the supreme American example, may easily have been the most formally inventive novelist this country has ever produced, but he never has attracted even a fraction of the adulation and mythification assigned here to Hemingway and Fitzgerald. The big-city sensibilities that tend to rule cultural hierarchies are generally too tied to trends and other social currencies to cope with regional geniuses, eccentrics who reinvent their art from the ground up and live by their own timetables. So it shouldn’t be surprising that such supposedly esoteric figures, steeped in the intricate folklores of their respective cultures––Faulkner’s Mississippi, and Paradjanov’s Ukraine, Georgia, and Armenia––are often appreciated first in countries other than their own.

Despite frequent references to Eisenstein during his press conference in Rotterdam, Paradjanov came across as earthy and instinctive rather than intellectual––a short, bearded, and ebullient Armenian Mr. Natural who typically responded to each question with a manic, charismatic 45-minute performance that only had a glancing relation to the query posed. His half-hour short on the primitive painter Pirosmani, which one hopes will be exported soon, obeys almost none of the rules of etiquette that our pendantic art appreciations call for: canvases are accompanied by sound effects (neighing horses, chirping birds, tolling bells), subdivided into whimsical collage and montage effects, and restaged and/or reshuffled in surreal live-action tableaux that recall Joseph Cornell boxes. Yet the film succeeds precisely where such urban sophisticates as Godard (Passion), Resnais (Van Gogh, Guernica), Clouzot (The Picasso Mystery), Minnelli (Lust for Life), Huston (Moulin Rouge), and Gorin (Routine Pleasures) fail––in filming a painter’s work without giving us either a gliding Cook’s tour or a mincemeat dissection of it, guiding without shoving us into a position where we can simply (or complexly) look at it.