|

Abderrahmane Sissako's two films La Vie Sure Terre and Heremakono draw on the local environment and its inhabitants to create a distinctive architecture with which to articulate larger questions such as the devastating legacy of colonialism, the unequal relationship between Africa and Europe, the despair of Africans living in the Diaspora, as well as the impact of globalization. These films are contributing to the development of an African Film language although by no means the only one. Visionary Senegalese filmmaker the late Djibril Diop Mambety spoke of the beauty that African landscapes offer filmmakers and the richness of images. He talked of creating an African film language "that would exclude chattering and focus more on how to make use of visuals and sounds1," as he did in Hyenas. This article will examine the filmic devices used to create a distinctive Saharan architecture using sound, cinematography and movement. It will also explore how the architecture in these films develops an African film language based on the natural environment as a conduit to comment on issues of colonialism, globalization, and the pain of the Diasporic exchange. Abderrahmane Sissako's two films La Vie Sure Terre and Heremakono draw on the local environment and its inhabitants to create a distinctive architecture with which to articulate larger questions such as the devastating legacy of colonialism, the unequal relationship between Africa and Europe, the despair of Africans living in the Diaspora, as well as the impact of globalization. These films are contributing to the development of an African Film language although by no means the only one. Visionary Senegalese filmmaker the late Djibril Diop Mambety spoke of the beauty that African landscapes offer filmmakers and the richness of images. He talked of creating an African film language "that would exclude chattering and focus more on how to make use of visuals and sounds1," as he did in Hyenas. This article will examine the filmic devices used to create a distinctive Saharan architecture using sound, cinematography and movement. It will also explore how the architecture in these films develops an African film language based on the natural environment as a conduit to comment on issues of colonialism, globalization, and the pain of the Diasporic exchange.

La Vie Sur Terre is a visual poem as well as a strong statement on Africa and globalization as we entered the 21st century. The film was shot on the eve of the millennium in Sissako's father's hometown of Sokolo in Mali, near the southeast corner of Mauritania. The making of the film came out of the 2000 Vue Par, a European television series which invited ten outstanding independent producers to imagine the last day of the present century in their own countries. La Vie Sur Terre shows the limitations of connectivity in a town that has only one telephone line and where modes of transport, like many places in the developing world, are still mainly limited to foot, donkeys, and bicycles. Sissako's challenge was to comment on the impact of the 21st century when in some ways Sokolo hadn't even entered the 20th century. Yet Sokolo is far more connected to the modern world than a first glance suggests.

The film is accompanied by a soundtrack and voiceover that includes Salif Keita's evocative rendering of Folon: The Past and is interspersed with quotations from the forceful work of Aime Cesaire, that endorse the words of the song.

Sissako then builds on the architecture of La Vie to create the hauntingly stark film Heremakono (2002) which at first just stuns the viewer with its beauty. It is set in a small town between the desert and the ocean on the coast of Mauritania where, like Sokolo, nothing much seems to happen. The camerawork painstakingly illustrates the beauty of the desert and the dilapidated little town where many would see nothing but sand and decay.

|

|

As in La Vie Sur Terrre (1998), Heremakono is a carefully orchestrated visual poem that weaves together the director's contemplation on migration, alienation, globalization and belonging and witnesses the pain that Africans can suffer as a result of the Diasporic exchange. Like La Vie Sur Terre, under the surface of this desolate beauty are layers of subtle commentaries on life. The setting is not untouched by contemporary life, although most in the community have few luxuries, some are only now receiving electricity with the help of the elderly Maata and his young assistant Khatra rigging up light bulbs. As Arjun Appadurai points out, globalization is not necessarily a process of homogenization, consequently, as the flotsam of global consumerism reaches the shores of the village, the inhabitants then appropriate it as their own2.

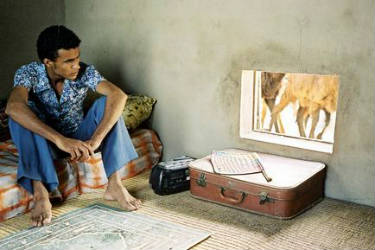

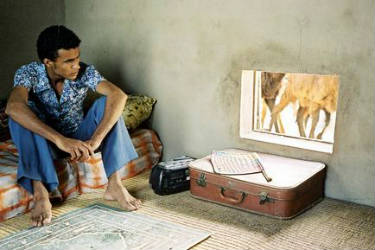

{niftybox background=#8FBC8F, width=200px} Sissako's cinematography is integral to the films' architecture as it resists colonial imagery and re-articulates African realities.{/niftybox}The film takes place in Nouadhibou, a transit city where Sissako himself spent time before going to film school in Russia. The local housing is temporary. This type of temporary housing in Mali is called Heremakono, (waiting for happiness) which is how the film gets its title. (Notes from the director). Heremakono is also the name of a town in Mali which is mentioned in the script.Heremakono and La Vie Sur Terre are hard to fit into the Manthia Diawara's typology of African cinema although they contain some of the elements of social realism, they are far less didactic than, say, the films of Sembene. But they are nonetheless infused with Sissako's views on the relationship between Africa and its Diaspora. While natural light is important aesthetics in La Vie, in Heremakono light is central to the film both aesthetically and symbolically, from the natural light of the desert, to that of a single light bulb, to the metaphors that the light bulb represents. The wind gives movement and sound to the film. The constant brisk breeze moves billowing pieces of cloth and ripples the shimmering of people's clothes without which the screen would look very still.In both films Sisakko uses movement to animate the stillness of the surroundings or still shots to keep the viewers attention. Goats, people and bicycles moving across the screen in La Vie, while in Heremakono similar movements are portrayed through the eyes of the protagonist Abdallah, looking out of a ground level window in which we see only the legs and feet of passers by.

{niftybox background=#8FBC8F, width=375px} globalization is not necessarily a process of homogenization, consequently, as the flotsam of global consumerism reaches the shores of the village, the inhabitants then appropriate it as their own {/niftybox}The constant breeze also creates movement as, for example, pieces of billowing cloth flap across still shots. Brightly colored local cloths are an important part of Sissako's mis-en-scene. They provide bursts of color in contrast to the earth tones of buildings and pathways, and to the sand. Both films set the warmth of Saharan architecture against the cold grey ones used in shots of Europe. Sissako's cinematography is integral to the films' architecture as it resists colonial imagery and re-articulates African realities. Deep focus shots follow a character walking into the distance in the desert, holding the camera until they are out of sight thus creating a sense of the vast local space and the slower passing of time.

Sissako does not use conventional narrative to tell his stories. In fact his films defy traditional film school theory. He sometimes holds the camera on an image when nothing much is happening or when conventional techniques would have ended the shot.

|